It wasn’t a crash landing – not technically. Arriving in Rijeka just felt that way, in that I was sleep deprived, confused, and could barely understand a lick of the Northern Adriatic dialects of Croatian that now surrounded me.

I met with B— and with D— and we crashed into a cafe. It was somewhere off of the square with this odd fountain: not an abstract sculpture, but a real piece of machinery from the Hartera Paper Factory that had been repurposed into public art.

Fountain made from Hartera Paper Factory machinery.

D— was a former worker in the Rafinerija Nafte INA, Croatia’s only oil refinery. An old man now, he was a regular contributor to the factory newspaper during the socialist period. I feel real regret that I couldn’t take notes, or comport myself well in Croatian at the time. All I could make out was his repeated, emphatic claim: there was no censorship, his words were never repressed, he was always able to communicate about the problems he observed in the factory. During the transition period, that’s when they started to cover up plaques and change stories around. He thinks I’m looking for stories about repression, about a big bad evil socialist state controlling the free speech of its subjects (I’m not, but I’m from Canada; it’s a fair expectation to have). So he repeats himself – it wasn’t like that, he wrote honestly.

Overlooking the beach and soccer stadium.

Next thing I remember, we’re back in the car and B– is driving. Her kids are in the back seat, we’re driving to the beach, but stopping on the way to look at workers’ housing that was built during the early 1960s. The housing was meant to be temporary, for workers who were waiting to leave Yugoslavia for Germany and send back remittances: now it’s all abandoned.

Beach at night.

The next day, I’m in the archives. I couldn’t pull any files from the refinery, so I switch gears to look at the workers’ council meeting minutes from the Hartera Paper Factory. I also look through their factory newspaper. I select a few issues from landmark years, and start combing through the paper.

Factory newspaper from the Hartera paper factory (Tvornica Papira Hartera). This article discusses the reconstruction of engineworks in the factory. National Archives of Rijeka.

It’s thorough, it’s real reporting on the day to day issues – and larger planning problems – within the Paper Factory. They’re unsure if they want to close one wing of the factory and reinvest in new machinery. A real firestorm of a debate ensues, as different workers write in with their perspectives. The workers’ council and managing board all get pulled into the debate.

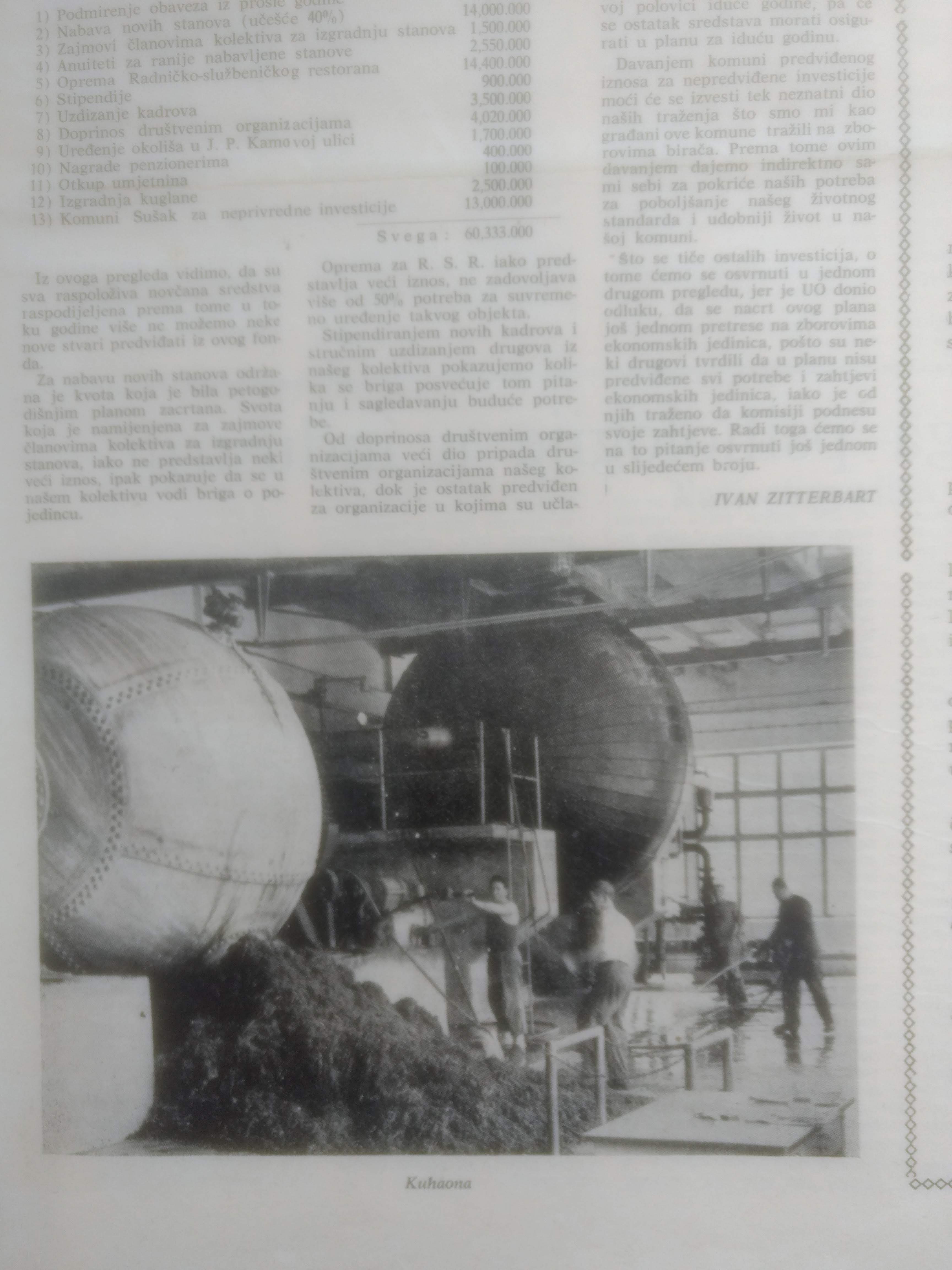

Factory newspaper from the Hartera paper factory (Tvornica Papira Hartera). This article presents a tabulation of expenditures, and contains a photograph of pulp roasting machinery. National Archives of Rijeka.

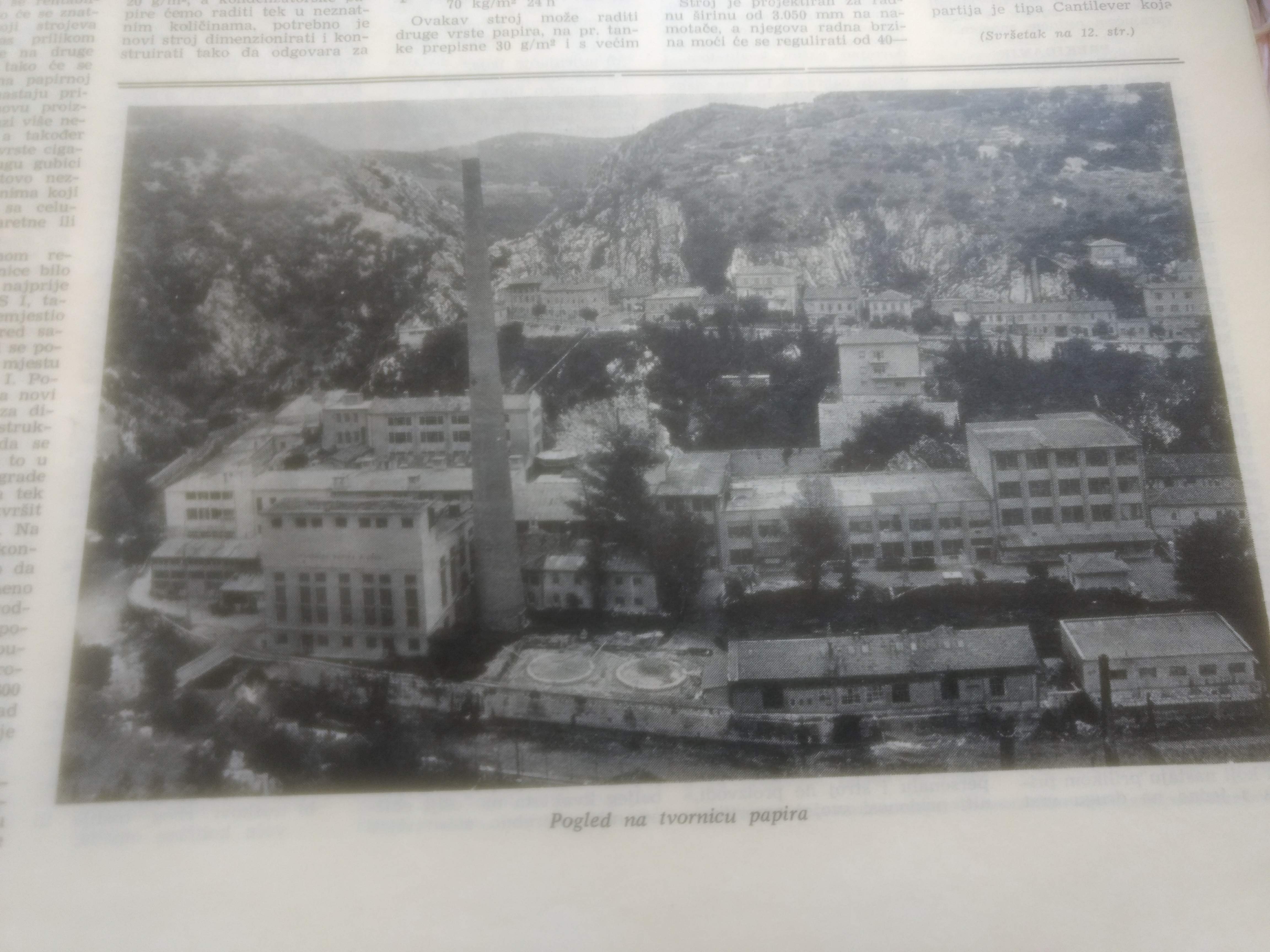

It’s a beautiful factory, or it used to be.

Exterior of the Hartera Paper Factory, mid-1960s.

It takes me a long time to realise that the factory is still standing. Although it was shut down sometime after the civil wars, the actual built structure of the Paper Factory is still around. It’s actually walking distance from the archives, though it takes a meandering path.

Empty factory buildings.

The factory is indeed, a wreck.

Empty factory interior.

It’s completely abandoned.

Further abandoned sections of the factory.

Many of the old machines are still lying there too.

Rusted factory machines.

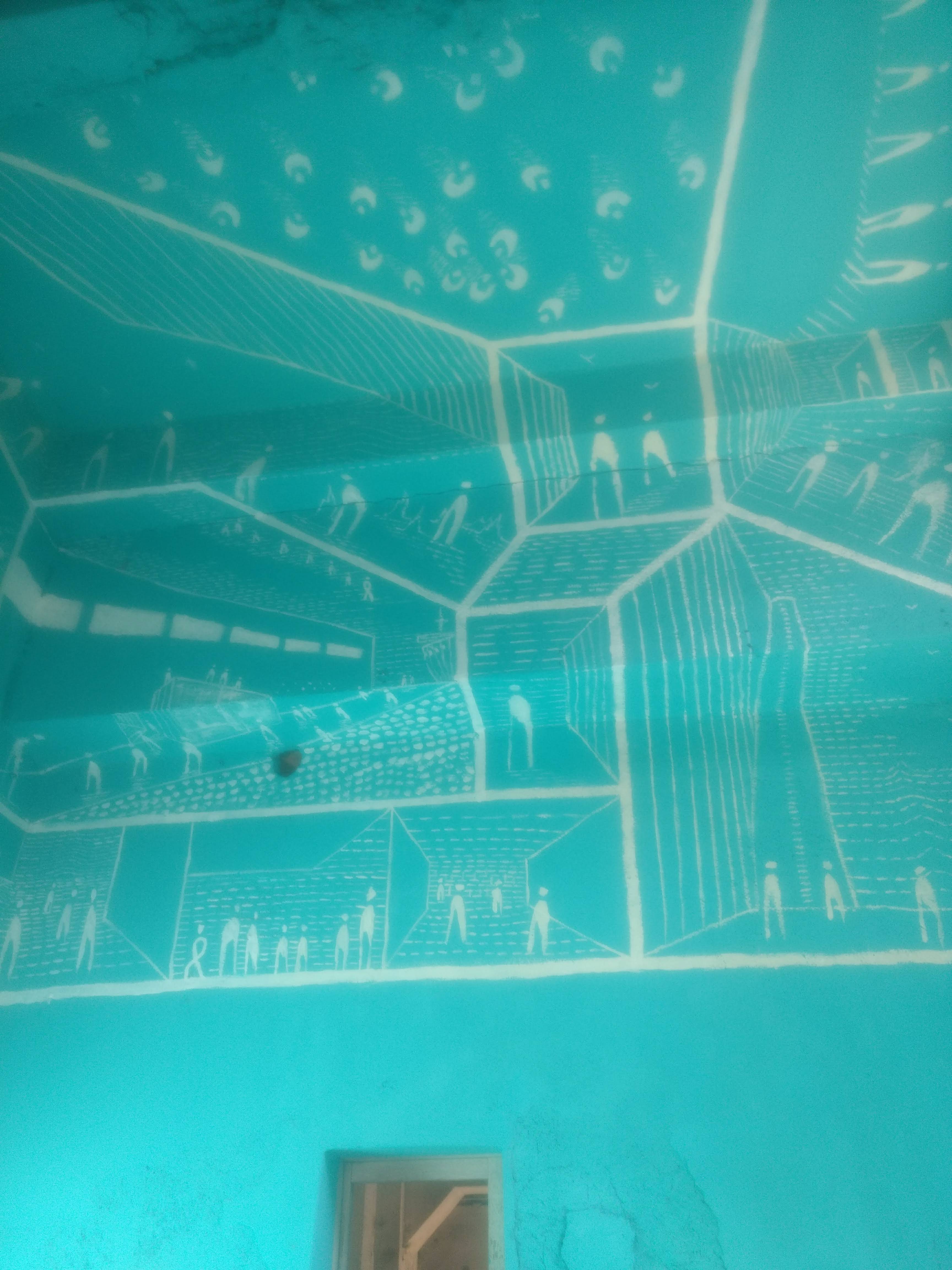

I keep exploring the carved out guts of this factory, one that used to employ so many thousands of people and single handedly produce 8% of the world’s cigarette paper. I finally come to an area that had been graffitied over.

Graffiti inside the abandoned factory.

Who are these people in the graffiti? Where are they going? Trapped as they seem in highways that are also boxes – what ghostly infrastructure surrounds them? I’m still not sure.